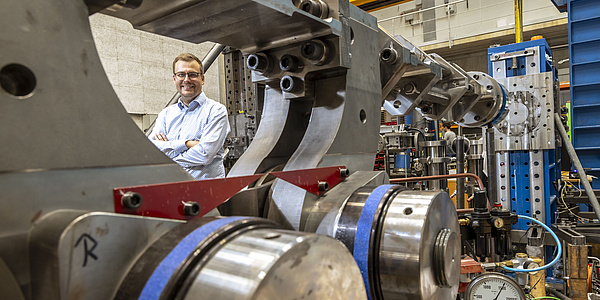

Christian Trapp: “For me, a beautiful machine is simple.”

Where and how did your scientific career begin?

Christian Trapp: I come from Heidelberg. You can certainly tell by my pronunciation. I lived there for a very long time, but studied mechanical engineering in Karlsruhe and Stockholm. I then studied for my doctorate at Stuttgart University.

Is that also when you started to get involved with engines?

Trapp: Yes. At that time, combustion engines were slowly creeping into my life because the institute where I was doing my doctorate was working intensively on them. I was very lucky because the first direct-injection Otto engines were being made at the time. This was a new technology that many OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) were working on. Our institute had a great deal of expertise in this area and we were able to work very closely with Mercedes. I was also able to gain my first management experience as a doctoral student because I led a team of technicians on the test benches as well as graduate students. I arranged my doctorate around a project for the Research Association for Combustion Engines, which involved optimising engines through the use of simulations. This is still a very important topic for me today.

Simulations?

Trapp: The topic of simulation-based development and optimisation is extremely important to me, as the complexity of systems and machines is constantly increasing. This involves more efficiency, fewer pollutants, less noise and vibration, lower costs and ever shorter development cycles. Simulation-driven development enables us to achieve this and expand the limits of physics further and further.

It’s not really the vehicle itself that fascinates me, but the engines.

(Christian Trapp)

But you have always tried to reduce pollutants, haven’t you?

Trapp: In my early university days, the main thing was about saving fuel and thus reducing CO2. The emphasis was then put the efficiency of the engines while at the same time complying with emissions regulations, such as the EURO regulations, which have since become more and more strict up to EURO 7 and are increasingly becoming the focus of developments.

What interests you so much about vehicles that you dedicate your scientific career to them?

Trapp: It’s not really the vehicle itself that fascinates me, but the engines. And in particular what’s going on inside the engines. I deal with thermodynamics, combustion and flow – and also the regulation of all these processes. I want to find new concepts that make them more sustainable. In other words, reduce consumption, reduce CO2 and reduce pollutants.

What happened after your time at university?

Trapp: I was able to make contacts in the automotive industry at university and then worked for Bosch. I completed a management trainee programme there and learned a lot about soft skills and leadership. During this time, I also spent six months working for Bosch in the USA and supported Cadillac on a project – so again, a very nice engine in a very nice car.

Is gaining experience abroad an important thing for you?

Trapp: Yes, very much. That’s what I’ve always tried to do. I did an internship in Singapore during my studies and wrote my diploma thesis at KTH in Stockholm. Later on, my teams were always international and based all over the world. The international environment and worldwide contacts are very important to me. We are one world and we’re all human beings. We should work together for a sustainable future and a sustainable environment – a sustainable world for everyone.

What happened after Bosch?

Trapp: After four years, I joined Ricardo Engineering as Chief Engineer for Otto engines in German-speaking countries. I was responsible for two BMW motorbike projects – again, combustion processes and thermodynamics. After that, I not only changed the company, but also the engine size. I started at Jenbacher in Austria, which produces large engines for power generation and combined heat and power plants. I went to Jenbach – a town in Tyrol – as head of the thermodynamics department and ended up with global responsibility for performance, emissions and controls for all Jenbacher and Waukesha engines as well as for energy systems containing these engines. At this time, I began working closely with the LEC (Large Engines Competence Center) and the Institute of Thermodynamics and Sustainable Propulsion Systems at Graz University of Technology (TU Graz). So I already have a long-standing relationship with Graz and know the city and TU Graz here very well.

How did you feel in Austria?

Trapp: Back then, I lived near Innsbruck with all the wonderful mountains, where I feel very much at home. The first question in the interview was of course “Can you ski?” (laughs). So my boss at the time set priorities right from the start. It suited me very well and I had a great time. But I always wanted to work more with young people and so I also gave lectures at the management centre in Innsbruck and at the university in Esslingen.

The first question in the interview was of course “Can you ski?”

(Christian Trapp)

The offer from the University of the Bundeswehr Munich was therefore very tempting, with research and teaching at the highest level, and putting technology and people at the centre. I was then appointed Professor of Vehicle Propulsion and had a lot of opportunities to shape things. There was an old laboratory that had been empty for a good six years. Luckily, there were the necessary funds to rebuild everything, which I did: Engine test benches, roller test benches, fuel cell test benches and also a demonstrator for a holistic energy system with photovoltaics, small wind turbines, battery systems, electrolysers, hydrogen storage, combined heat and power plant, fuel cells and bi-directional integration of vehicles... a large, exciting development project as part of the Research Centre for Mobility and Renewable Energies, which I co-founded, with funding from the German government for 6 years. There were 17 professors and almost 100 employees at the university, plus many industrial partners.

We conducted research on mobility and propulsion systems, as well as energy sources and energy systems of the future that will be required for them, and made them accessible in the truest sense of the word. There was a particular focus on these sustainable and resilient energy systems.

In what way?

Trapp: It was all about distributed power – in other words, distributed energy systems for a sustainable future. For me, the resilience of these systems is important, especially when they are used in critical infrastructure such as hospitals, water supplies, data centres, fire services or police forces. This resilience is becoming increasingly important, as the war in Ukraine shows us, where the first thing that was attacked was Ukraine’s energy supply. However, attacks do not only have to be physical military attacks, they can also be sabotage, terrorist attacks and cyber attacks, as we are seeing more and more of in western Europe.

If you know the book called Blackout, this scenario is much more realistic than we would like to admit. What happens if our critical infrastructure, hospitals, police, fire brigade, supermarkets and banks suddenly stop working? Then things gets difficult. We need to think very carefully about how dependent we are on energy and what happens when it is no longer available, and how we can strengthen our resilience and ability to operate in a crisis – and very quickly.

What happens if our critical infrastructure, hospitals, police, fire brigade, supermarkets and banks suddenly stop working?

(Christian Trapp)

This is a very important and exciting topic, one on which I have already worked at the University of the Bundeswehr closely with the LEC here in Graz, especially in the development of methods and simulation for the optimisation of such energy systems. Graz also has a great deal of expertise in this area.

You mentioned hydrogen systems earlier. Was that also a key focus?

Trapp: We have been conducting parallel research into hydrogen-based combustion engines – for combined heat and power plants on the one hand and for truck and bus engines on the other. These can make a valuable contribution to sustainability, based on a technology that is well known to us.

Together with BMW, I have also developed a concept for a serial hybrid vehicle and built a corresponding demonstrator vehicle. This can include hydrogen engines or fuel cells, for example, which are optimally combined with batteries and electric motors. We have also investigated other sustainable fuels, such as ethanol, methanol, OME and octanol, which can be used in relatively conventional combustion engines.

The topic of simulation methods was and is very important for all of this: the development of new models and then also the validation of the simulations. They have to be validated so that we can work predictively and obtain reliable results.

And now you’re at TU Graz.

Trapp: As I said, I already knew the institute and the city very well. On the one hand, it was very difficult for me to leave Munich because I had set up a lot of things there. But Graz has always been close to my heart. I like the institute, I like the people and the city. It’s a fantastic opportunity and I am very honoured to have been given it.

How would you like to organise research in the future?

Trapp: My topics are perfectly suited: sustainable propulsion systems and thermodynamics, various engines with sustainable fuels, hybrid propulsion, complete propulsion concepts for the future of vehicles, sustainable and resilient energy systems. That is exactly my focus. And I’m also familiar with large engines. We have a great institute here with all the facilities, excellent employees and department heads. At the same time, close integration and cooperation is also possible with the LEC and HyCentA, so that we can conduct research into sustainability and resilience in large, holistic systems. This enables us to create a basis, gain new insights and publish them. Additionally, we can press ahead with application-oriented research and development with and for industry, thus strengthening business in Austria and Europe. Research secures our prosperity and a sustainable everyday life for the future.

At the same time, we need to get young people interested in these topics. Despite AI and computer science, we also need mechanical and electrical engineers who know how to use AI and IT and so on. We need balanced teams with a significantly higher proportion of women than we have in Austria today. Interestingly, in countries like Italy, France and Spain, the number of women in mechanical engineering is significantly higher than in Germany, and we need to ask ourselves how we can improve conditions here accordingly.

Despite AI and computer science, we also need mechanical and electrical engineers who know how to use AI and IT and so on.

(Christian Trapp)

Technology and training in this area also has to do with ethics – I don’t have to do everything I can do and I should do everything I can to be as sustainable and resource-efficient as possible, for the benefit of everyone. Our colleague Helmut Eichlseder and his team have built up an impressive organisation here over the last 25 years, and they have left very big footprints behind. I will attempt to fill them in this constantly and ever faster changing world and, together with all my colleagues, to keep the Institute and TU Graz as beacons of top-level research in the world and to lead them successfully into the future.

And one final question: What do you think makes a beautiful machine, a beautiful engine – which you mentioned at the beginning?

Trapp: When it’s simple. But at the same time highly efficient in terms of fuel consumption, for example, and emits no pollutants. The simpler and more resource-efficient the technology we can use to achieve our goals, the better it is for me.