Pregnancy in the Research Focus of TU Graz

![[Translate to Englisch:]](https://www.tugraz.at/fileadmin/_processed_/9/c/csm_placenta-banner-by-wolf-tugraz_0ff2172605.jpg)

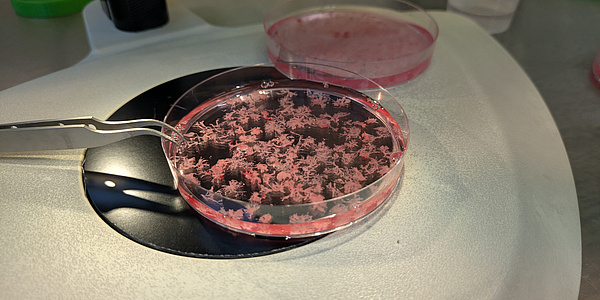

Two small, pale, living structures floating leisurely in a bioreactor. The bioreactor functions as a controlled bioincubation system that simulates and precisely regulates the environment of the human body. The small structures are mini-organs – more precisely a mini-placenta and a mini-uterus. Both were cultivated from human cells and have been developing here in the laboratory for a few weeks.

“We want to use these mini-organs to investigate pregnancy complications at various stages in a controlled manner and test drugs safely,” explains Sahar Ghorbanpour, who has headed the HerPlacenta working group at the Institute of Health Care Engineering at TU Graz since January 2025. The removal of placental tissue or the testing of medication during pregnancy is not possible for ethical reasons and can jeopardise the life of both the mother and the child. Therefore, many important questions about pregnancy complications and drug safety remain unanswered, although both are crucial for the health of mother and child. At the same time, pregnancy complications in humans cannot be reliably reproduced in animal models because pregnancies take completely different courses. The mini-organs are intended to provide a remedy and enable safe and controlled research in the laboratory.

These mini-organs grow in the laboratory and float freely in a bioreactor in a precisely adjusted nutrient solution. The system creates microgravity-like conditions that minimise mechanical stress so that the cells can organise themselves more naturally and develop structures that are very similar to real human organs. “They grow very quickly and develop well,” says Ghorbanpour, who works with a global network of research partners. Pregnancy complications vary greatly around the world, she explains, which is why samples from different countries are so important. “Women generously provide us with their samples during one of the most profound and vulnerable phases of their lives,” says the researcher. Pregnancy can be an extraordinary experience, but it is also physically and emotionally exhausting – especially when complications arise. For Ghorbanpour, this reality is not only scientific, but also deeply personal. As a young woman, she suffered from endometriosis, a condition that can increase the risk of pregnancy complications, and completed her doctoral thesis while pregnant with her first child. “I was lucky not to experience any complications,” she says. “But many of the women I worked with had a very difficult path ahead of them. This work has the potential to transform maternal and foetal health research and lead us to a future where pregnancy care is safer, better informed and globally accessible – so that no woman is overshadowed by preventable complications on her journey to motherhood.”

“It’s time it becomes one of the central questions of research.”

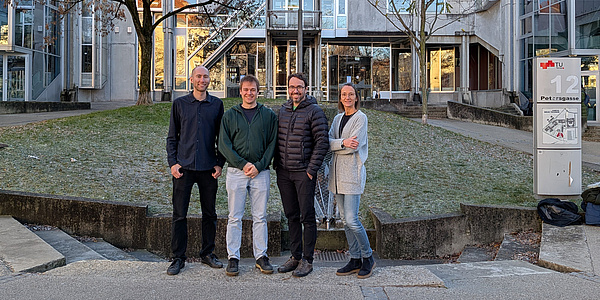

She made an important breakthrough in her earlier research work at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia. She linked biomarkers identified in plasma samples from pregnant women with early-onset pre-eclampsia to the first nanoparticle-based point-of-care device for the early detection of this complication. Building on this work, she now wants to further develop her novel mini-organ platform at TU Graz in order to use it for the discovery of biomarkers and the testing of drugs and ultimately to create more precise diagnostic tools. In addition to biotechnologists, the team also includes experts from the fields of nanotechnology, biomaterials, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine as well as a partner company from industry.

Another important goal of the young researcher is to get research into pregnancy and women’s health out of the niche it has been in for years: “It’s time it becomes one of the central questions of research.” In the future, the working group plans not only to look at individual organs, but also to investigate how different organs communicate with each other during pregnancy. The group also aims to extend its work to pregnancy-related cardiovascular diseases by developing miniature models of beating hearts.

Understanding trophoblast cells: the cells that make placenta formation possible in the first place

Julia Fuchs’ research at the Institute of Biomechanics starts at the very beginning of pregnancy. She is investigating how trophoblast cells behave in the human body. These cells migrate into the maternal veins and arteries and enable them to open to supply the embryo. They are responsible for the development of the placenta.

These cells are unique in the human body because they are invasive in a controlled manner: They can migrate into maternal tissue, but stop this process after a certain period of time. In some respects, they resemble cancer cells, whose invasiveness is uncontrolled and damages the body. It is precisely this difference that makes trophoblast cells particularly interesting from a scientific point of view. “We use placenta samples from the first trimester of pregnancy and primary cells from blood vessels of a donor body to build a very human-like model in the laboratory, which we then use to investigate the migration of trophoblast cells.” In particular, the focus is on the extent to which the cell type lining the maternal blood vessels influences the behavior of trophoblast cells and how environmental conditions such as the oxygen content in the blood affect the cells. “With this research, we want to better understand the process itself, but also find biomarkers that make pregnancy complications easier to recognise and therefore treat.” Julia Fuchs works closely with the Department of Cell Biology, Histology, and Embryology at the Medical University of Graz, which provides access to human samples as well as key cell biology and medical expertise.

“We use placenta samples from the first trimester of pregnancy and primary cells from blood vessels of a donor body to build a very human-like model in the laboratory, which we then use to investigate the migration of trophoblast cells.”

Simulation of blood flow in the placenta from a mathematical perspective

Stefan Posch, who heads the CD Laboratory for Physics-driven Machine Learning in Industrial Applications at the Institute of Thermodynamics and Sustainable Propulsion Systems, also believes that research in the field of women’s health and obstetrics should play a much more central role. “I have been interested in medical questions for a very long time. While looking through the work of the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics led by Christian Wadsack and Hanna Allerkamp at the Medical University of Graz, I noticed that they work with the same equations and the same mathematics as we do,” he explains. A surprising realisation that led to a collaboration with Malte Rolf from the Institute of Biomechanics and a joint master’s thesis. “In this way, we want to build up fundamental expertise in this very complex field.”

And the human placenta with its fine structures and dense blood vessels is particularly complex. “Translating this subtlety into a model that makes verifiable simulations possible is incredibly complex. I have seen that up to now we have had to work with many simplifications that are not entirely correct,” explains Posch. The researchers would like to change this in the distant future. Because there is still a lot of research work to be done before then, even if “the basic maths behind a simulation of an engine is the same as behind the human placenta.”

![[Translate to Englisch:]](https://www.tugraz.at/fileadmin/_processed_/9/c/csm_placenta-banner-by-wolf-tugraz_2320ad7ad7.jpg)