Bacteria as Bodyguards for Food Crops

Alternatives to sprays

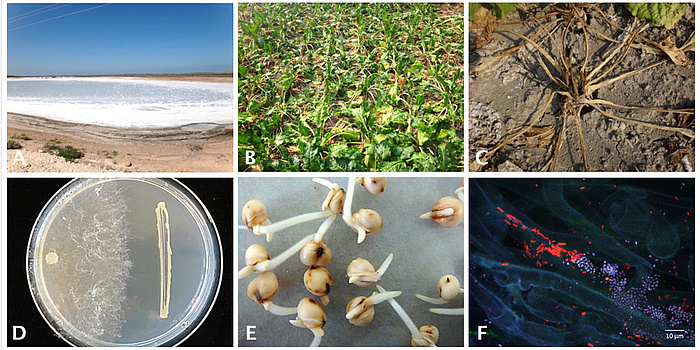

But what exactly is behind the project? It’s about finding alternatives to sprays, which are polluting agricultural land. The objective of Zachow and her team was and is to be able to fight off pests in a natural way. Zachow explains how the first “bodyguards for precious seeds” originated step by step: “We took samples of mosses, lichens and other plants from their natural habitats in the Alps and obtained their associated microorganisms. Together with their hosts they withstand extreme conditions, such as acidic soils, lack of nutrients, intensive UV radiation and extreme dryness. In a second step, the obtained microorganisms were applied to the seeds of crop plants. The latter accepted all the microorganisms that they needed for protection. The seeds were planted and two weeks later the root was removed. Individual microorganisms were then isolated which could both live in extreme habitats and on the crop plants. In short, this method, which is a result of the cooperation between Graz University of Technology and acib, uses the features of microorganisms which come from extreme locations, and which both promote growth and protect against environmental stress, for crop plants. This procedure can now be transferred to many other systems. “It is conceivable, for example, to protect plants against dryness or salinity. “You seek out microorganisms which live in desert regions and which are suitable for the desired crop plants,” says Zachow. In the framework of an EU project at Graz University of Technology, a high yield of vegetables was obtained in the salt steppe of Uzbekistan using an active bacterium. The bacteria each plant needs adapts to the host and protects against extreme conditions. Zachow continues, “It works in a similar way to the human bowel, whose flora support the health of the individual.” The bowel flora are colonised by bacteria and represent a complex bacterial ecosystem. At the end of the whole process is a seed which is surrounded by a “bacteria hull.”

Climate change and sprays

According to Zachow, this process should mitigate the effects of climate change. Failed harvests occur more often because hot spells and droughts create problems for farmers. According to climate researcher David Battisti, a study by scientists at the University of Washington shows that increasing temperatures have huge effects on grain farming. According to data from the researchers, in the tropics alone, the maize and rice harvests will be reduced by 20 to 40 percent by 2100 due to the higher temperatures. A second aspect should also not be ignored. Every year agricultural areas are infested by pests on a massive scale despite the use of sprays. At the same time many beneficial organisms suffer from the use of chemicals. For instance, reports surfaced this year of bees dying due to the use of Neonicotinoids. 28.5 percent of domestic bees did not survive the last winter alone due to the temporary suspension of the prohibition against neonicotinoids. This was reported by Graz zoologists. “Not only humans, but also crop plants are challenged by climate change. On top of this can be added a lack of nutrients through the use of monocultures,” says Zachow, who in the course of her research on the project has noticed a rethinking on this topic on the part of domestic farmers.

A look at the future

Master’s student Christina Laireiter characterises microorganisms and creates different cocktails. And, as mentioned earlier, domestic farmers are impressed by the results. And now the research results should be even tastier for them, since food will be much safer. After all, “We want healthy plants and, in the final analysis, healthy food. A functioning biological plant protection system is a genuine alternative to sprays,” concludes Zachow. Competition is big for the methods of acib. The chemical industry turns over some 40 billion euros per year on “crop protection products”, and a third of this ends up on fields of the European Union.

Kontakt

Univ.-Prof. Dipl.-Biol. Dr.rer.nat.

Head of the Institute of Environmental Biotechnology, TU Graz

Petersgasse 12/I, 8010 Graz, Austria

Phone: +43 316 873 8310

<link int-link-mail window for sending>gabriele.berg@tugraz.at, <link http: www.ima.tugraz.at>www.ima.tugraz.at Christin ZACHOW

Dipl.-Biol. Dr.rer.nat.

Senior Scientist, ACIB GmbH

Petersgasse 12/I, 8010 Graz, Austria

Phone: +43 316 873 8312/8422

<link int-link-mail window for sending>christin.zachow@tugraz.at, <link http: www.acib.at _blank int-link-external external link in new>www.acib.at