Introduction

The global situation the world is going through since the beginning of this year has fundamentally affected all areas of life, having had a big impact on a collective and an individual level. At the outset people witnessed the spread of the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, throughout the Asian continent and subsequently throughout the whole world. Corona-specific life circumstances (e.g. quarantine, closed borders) and social practices (e.g. face masks, online meetings), initially believed to be far away, had to be integrated into one’s everyday life in the shortest time possible. In order to cope with the current corona crisis, governmental crisis management all over the world strongly focuses on the development of new vaccines or new medication. Yet, the pandemic crisis also affects the general public’s mental health. As it suddenly confronts each one of us to our own mortality, it can lead to mental stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), no matter whether directly exposed to it (e.g. patients, doctors) or indirectly confronted to its repercussions (e.g. witnessing of chaotic social conditions, confinement, travel restrictions) (cf. Render Turmaud 2020).[1]

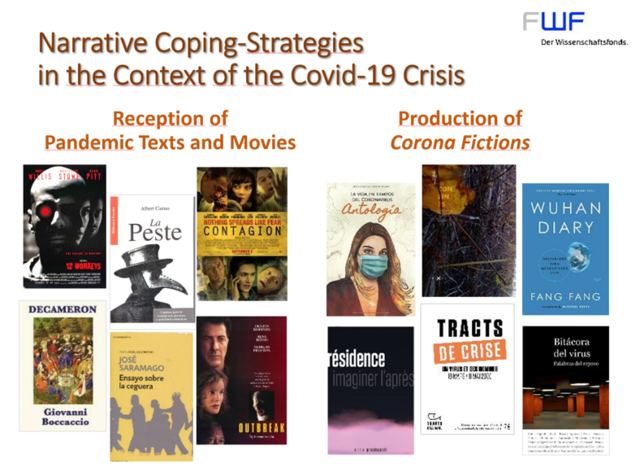

To master the potentially traumatic individual and collective experiences, crisis management also has to be accompanied by a self-conscious level of reflection on a cultural level. In fact, since the outbreak of the pandemic, we have not only seen a sudden increase of the reception of pestilence fiction, such as Albert Camus’s La Peste (1947) or Steven Soderbergh’s pandemic film Contagion (2011) (cf. Willher 2020, Mann 2020), but also an enormous increase of cultural production, particularly in the digital realm referring to the new life circumstances and social practices. By reading, watching, and listening to canonical and contemporary cultural productions many tried to understand what was going on and to find guidance for coping with the extraordinary situation (cf. Scrivner 2020). This increased turn to the consumption and creation of cultural production can be attributed to the capacity of literature and media “to impart its knowledge to its readers [and consumers] as experiential knowledge which can be reconstructed step by step, or even more, can be acquired by reliving it” (Ette 2016, 5). This capacity allows literature and media “to reach people and be effectual even over great spatial and temporal distances” (ibid.).[2]