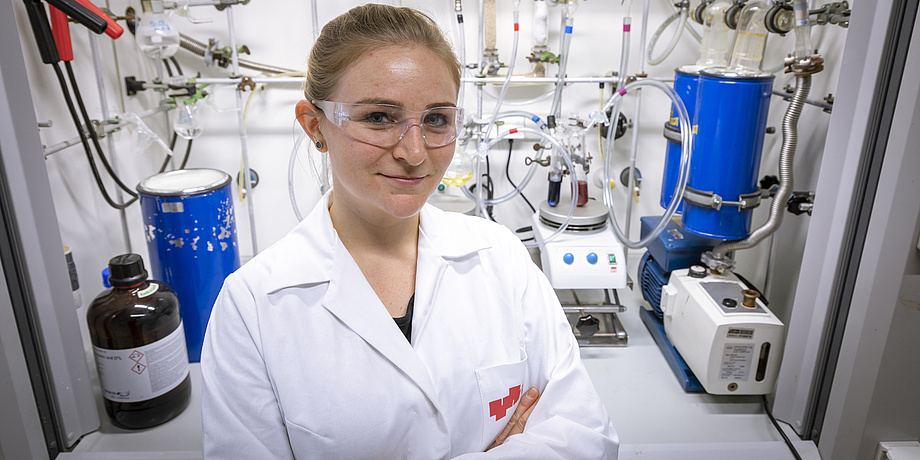

“I really can’t complain about the past year,” says Beate Steller with a grin. The 26-year-old researcher often smiles when she talks about her work in the brightly-lit laboratory in Graz’s Stremayrgasse. In 2018 she won several plaudits from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) for her research into inorganic chemistry: her master’s thesis won the Otto Vogl Award, which comes with prize money of EUR 5,000, and the Academy is supporting her dissertation with a DOC Fellowship.

“My work is incredibly leading-edge,” she says, leaning casually on a lab box containing a stack of cables, pipes and test tubes. A member of the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry, she works on model compounds which she uses to observe reactions on the surfaces of inorganic materials. “Observing surface reactions is really difficult, because there are no analytical methods available,” she explains. “So we have to use molecular models dissolved into solutions and observe them instead.” These insights are especially important when it comes to semiconducting metals, which are used to produce the majority of electronic components. “You can only optimise and enhance the materials if you understand these reactions,” she points out.

Professor Roland Fischer of the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry supervised her master’s thesis, and is now supervising her dissertation. “Beate has chosen an exceptionally complex topic for her doctorate. A whole series of starting compounds for the molecular model compounds need to be represented – some of them for the first time – and then we have to carry out research into new means of synthesis to create cluster compounds. A sufficient quantity then need to be represented so that we can analyse the model reactions. You often experience setbacks and frustration. But thanks to her skill and enthusiasm for experiments, Beate is making good progress,” commented Professor Fischer.

Beate Steller creates model compounds with which she can observe reactions on material surfaces.

Master’s and doctoral students at TU Graz enjoyed a particularly successful 2018. Among others, Christina Granitz won the Johann Puch Automotive-Award; Martin Goldberger and Andreas Hackl received an FSI scholarship; Imre Karacsonyi and Florian Arnold took the Railway Engineering Award, while Gerald Feichtinger and Johann Waldauf won research prizes from Österreichs Energie Forschung & Innovation. Daniel Gruss was presented with the Gesellschaft für Informatik (GI) Dissertation Award, the ACM SIGSAC Doctoral Dissertation Award and the 2018 Heinz Zemanek Prize. He also won a grant from the Forum Technik und Gesellschaft, alongside Niels Buchhold, Johanna Pirker, Moritz Lipp, Michael Schwarz and Christoph Haudum.

Ahead of the times

Born in Upper Austria, Beate Steller carries out cutting-edge research. But in her free time she prefers to take things more easily. “I like baking, do a lot of cooking and also needlework,” she explains with a smile. “Inside I’m a bit of a granny.” Above all, she has a passion for crocheting and sewing. Her most adventurous pastime is hiking in the mountains.

A native of Wels, she attended the Wirtschaftskundliche Realgymnasium der Franziskanerinnen – a grammar school focusing on business and economics – in Vöcklabruck; in her time it was an all-girls school, Steller tells us. After passing her school-leaving exams in 2011, Beate moved to Graz – now her adopted home. “Graz is big enough so there’s always something going on, but it’s also not too big, so you don’t feel lost.” She finished her bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 2014, followed by her master’s in 2017. During her studies Steller worked in a lab in England for six weeks, and she also spent a short time in the USA. “It was useful to get to know different approaches to chemistry and see how things work in a different lab,” she explains.

TU Graz offers bachelor’s and master’s degrees in chemistry. Both programmes are part of NAWI Graz, a partnership between TU Graz and the University of Graz.

When every day isn’t everyday

“My work is incredibly varied – basically I don’t have any routine tasks,” Beate explains. Each day she moves between the labs and her computer in the office. “The only thing I really do every day is turn on my vacuum pump in the mornings.”

As she puts it, she “stumbled” into research at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry: “I basically said the right thing at the right time in the right place in the inorganic chemistry lab in the third semester.” This caught the attention of supervisor Johanna Flock, who invited the gifted student to do a summer internship in the lab. “I really enjoy the challenges that inorganic chemistry presents. My research focuses on compounds that are unstable in air and in moisture,” Steller says, pointing out the appeal of her work. “ So I have to take a lot of factors into account before I start, I can’t just mix a few things together. I need to organise and think ahead – and that’s something I enjoy.”

Beate Steller at the glovebox: the interior is sealed, as the materials she works with decompose when they are exposed to air or moisture.

Visit Planet research for more research related news.